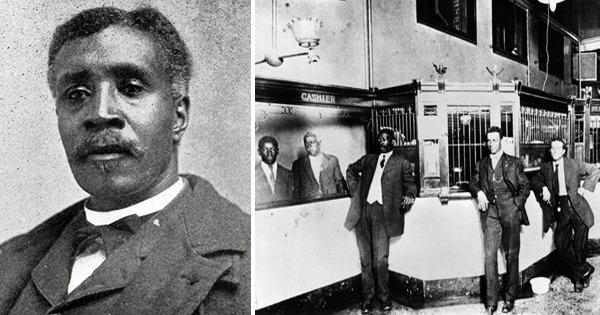

The Rise of a Visionary Leader

Reverend William Washington Browne was a trailblazer in African American financial history. Born into slavery in 1849 in Habersham County, Georgia, Browne experienced the harsh realities of oppression from an early age. However, his journey from bondage to becoming a banking pioneer exemplifies resilience, determination, and a profound commitment to racial upliftment.

After escaping slavery during the Civil War, Browne enlisted in the Union Army as a drummer boy. His exposure to military discipline and strategic thinking laid the foundation for his future endeavors. Following the war, he pursued education, becoming a teacher and later a minister in the Methodist Church. His role as a minister not only deepened his spiritual convictions but also strengthened his commitment to social justice and economic empowerment for African Americans.

Addressing Economic Disenfranchisement

During the Reconstruction Era, African Americans faced systemic barriers to financial independence. Discriminatory practices in banking and commerce left Black individuals and businesses vulnerable to exploitation. White-owned financial institutions often refused to serve Black clients or imposed restrictive policies that limited their ability to build wealth.

Browne recognized the need for a financial institution that would cater specifically to Black depositors, ensuring their economic security. His vision extended beyond banking—he sought to create a self-sustaining economic system that would empower Black communities through business ownership, financial literacy, and cooperative economics.

The Birth of the True Reformers Bank

In 1881, Browne founded the Grand Fountain of the United Order of True Reformers, a fraternal organization dedicated to uplifting African Americans through mutual aid, education, and economic cooperation. The organization initially provided insurance and financial assistance to its members but soon expanded into broader economic initiatives.

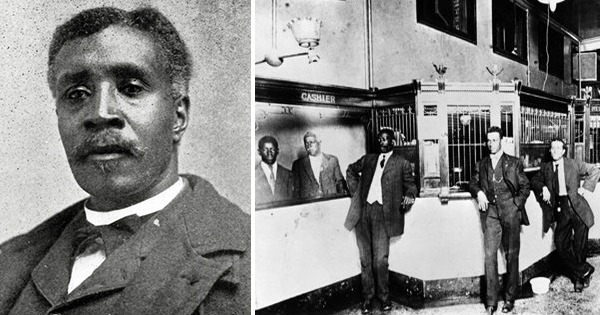

On March 2, 1888, Browne established the True Reformers Bank, the first Black-owned and Black-operated bank in the United States. Unlike other Black financial institutions that were often overseen by white administrators, the True Reformers Bank was entirely managed by African Americans. This distinction was critical, as it ensured that Black depositors’ finances could not be monitored or controlled by whites, a common practice in white-owned banks.

Overcoming Early Challenges

Launching a Black-owned bank in the late 19th century was fraught with obstacles. Skepticism from both Black and white communities, lack of initial capital, and discriminatory banking regulations posed significant hurdles. However, Browne’s strategic leadership enabled the bank to thrive.

To ensure financial stability, Browne implemented a strict lending policy. Unlike traditional banks that issued loans based on collateral, the True Reformers Bank only provided credit to members of the United Order of True Reformers. This approach minimized default risks and reinforced community trust.

Moreover, Browne devised an innovative financial structure that allowed the bank to operate without relying on white financial institutions. This self-sufficiency was groundbreaking at a time when Black businesses were often subjected to economic sabotage by white competitors.

Growth and Impact on Black Communities

The success of the True Reformers Bank was unprecedented. By the early 1900s, the bank had expanded its services, offering savings accounts, loans, and financial education programs. It played a crucial role in financing Black-owned businesses, churches, and educational institutions.

Beyond banking, the United Order of True Reformers operated a vast network of enterprises, including a real estate firm, a printing press, a hotel, and a retirement home for elderly African Americans. This ecosystem of Black-owned businesses not only generated wealth within the community but also fostered economic self-determination.

The bank’s headquarters in Richmond, Virginia, became a symbol of Black economic progress. It demonstrated that African Americans could successfully manage complex financial institutions, challenging prevailing racial stereotypes that portrayed them as incapable of economic self-sufficiency.

Lessons from the True Reformers Bank’s Demise

Despite its success, the True Reformers Bank faced mounting challenges in the early 20th century. Following Browne’s death in 1897, leadership changes and economic shifts weakened the institution. The Panic of 1907, a nationwide financial crisis, further strained the bank’s resources. By 1910, financial mismanagement and fraudulent activities led to its closure.

While the bank ultimately failed, its impact on Black economic empowerment was undeniable. It laid the groundwork for future Black-owned banks and inspired generations of African American entrepreneurs and financial leaders.

Browne’s Legacy and Modern Implications

Reverend William Washington Browne’s legacy extends beyond his banking achievements. He was a visionary who understood that economic independence was a crucial component of racial equality. His work underscored the importance of financial literacy, cooperative economics, and community-driven development.

Today, Black-owned banks and financial institutions continue to play a vital role in addressing racial wealth disparities. The principles established by Browne—economic self-sufficiency, cooperative business models, and financial education—remain relevant in contemporary discussions on economic justice.

The story of Browne and the True Reformers Bank serves as a powerful reminder that financial empowerment is a crucial aspect of social progress. By studying and building upon his legacy, communities can continue the fight for economic equity and inclusion.

Conclusion

From slavery to banking pioneer, Reverend William Washington Browne’s journey exemplifies resilience, vision, and unwavering commitment to Black economic empowerment. His establishment of the True Reformers Bank was a groundbreaking achievement that challenged systemic financial exclusion and provided a model for community-driven economic progress.

Though the bank’s lifespan was relatively short, its impact was profound. It demonstrated the power of Black entrepreneurship, financial autonomy, and cooperative economics. As modern discussions on financial inclusion and economic justice continue, Browne’s legacy remains a beacon of inspiration, reminding us that economic empowerment is a fundamental pillar of racial equality.

His story is not just a historical account—it is a call to action. By investing in Black-owned businesses, supporting financial literacy initiatives, and advocating for economic policies that promote equity, today’s society can build upon the foundation that Browne helped establish over a century ago.

Add Row

Add Row  Add

Add

Write A Comment